I look forward to your continued support this year as well.

In Sapporo, temperatures are higher than usual due to the effects of global warming, yet snow has accumulated to a reasonable extent.

However, once snowfall begins, it often turns into a severe snowstorm. Even within the city, whiteout conditions can occur while driving, making it impossible to see either ahead or behind, and creating extremely difficult driving conditions.

This too must be one of the manifestations of abnormal weather.

Now then, a new work has been completed.

It is in my usual size (full sheet: 1091 mm × 788 mm), drawn on Mermaid paper using soft pastels and colored pencils.

The title is

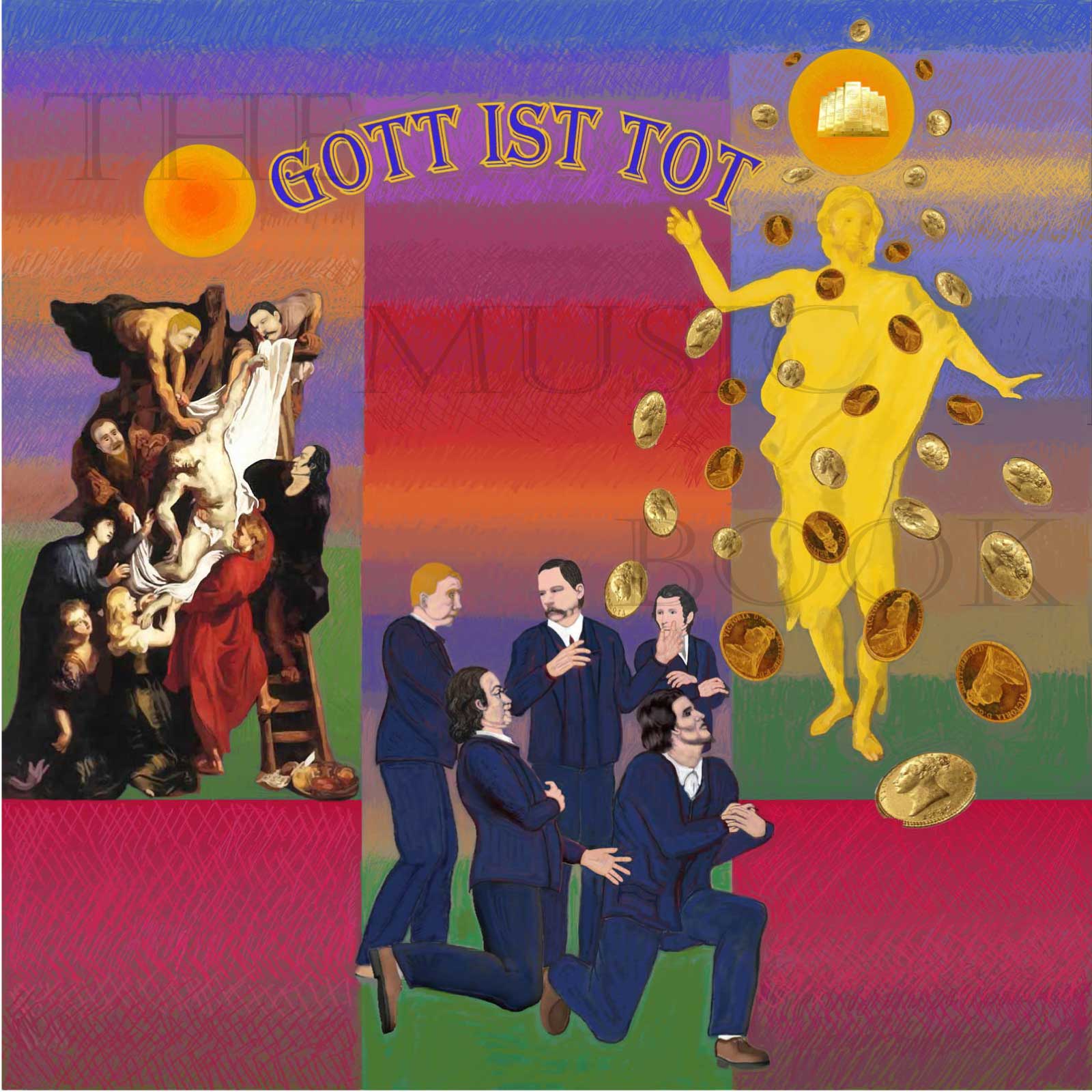

*“Apollo’s Chariot, 2026: The Ideal State of Things.”*

As you can see, this work can almost be described as an “abstract painting.”

The first work in the history of world art created after establishing a systematic theory for generating abstract forms!

Paintings on the theme of Apollo, the sun god of Greek mythology, were produced in great numbers by Odilon Redon using pastel and tempera.

Likewise, Eugène Delacroix, the greatest colorist of his time and a painter who orchestrated intensely musical color, created *Apollo Slaying the Python*, a work well known as a ceiling painting in the Louvre Museum.

Redon in particular stayed at Fontfroide Abbey in 1910, where he created his representative mural *Day*, depicting Apollo’s four-horse chariot.

The mastery required to control the four-horse chariot, something extremely difficult even for Apollo himself, and the fatal crash of the inexperienced Phaethon are depicted as paired opposites, like day and night, light and darkness.

During my university years, I encountered the pioneers of abstract painting, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

Kandinsky in particular is the painter I most admire and regard as my goal; however, I painted abstract works only once during my university days, and then only twice more about 35 years ago.

One reason I could not paint abstraction was that I did not yet understand the relationship between abstract form and music.

At the time, I believed that depicting concrete, physically existing humans or living beings was better suited to expressing clearer and stronger meaning. That was also one of the reasons.

There were, of course, several other reasons as well.

Are abstract form, color, and texture truly being created with conviction and necessity?

Historically speaking, there have been countless abstract painters.

However, aside from Kandinsky and Klee, are there any painters who work with true conviction and necessity—

who can explain, “This form necessarily becomes this shape, this color, and this texture according to this theory”?

Such painters are almost nonexistent.

In most cases, abstract paintings are created “somehow” or “intuitively.”

As a result, even when asked about the value of their own work, artists may say things like, “I am convinced that I am doing very good work right now,” yet I often feel that even they themselves do not truly know whether it has real value.

Many people create abstract paintings by linking them to music. However, very few can clearly explain what kind of relationship exists, or which elements of music theory they are using.

This is because they rely on a vague sense of “maybe it’s like this.”

Some time ago, I attended a web seminar titled “The Relationship Between Painting and Music,” hosted by the Japan Art Education Promotion Association (JEARA) and taught by a foreign lecturer from Musashino Art University.

There, participants attempted to compose music after viewing Monet’s paintings. When I asked, “Why did you compose that particular piece?” the answer was, “It’s the impression I received!”

I responded, “Then there is neither necessity nor conviction. I have discovered physical laws for translating painting into music, and I use them in my own production.”

The reply I received was merely, “That’s deep,” with no further surprise or sense of critical inquiry.

So then, was this work created with conviction and necessity, according to theory?

Naturally, that is what you would wonder.

My answer is, “Of course, exactly so.”

For every part of the canvas—every geometric element and every color that constitutes the composition—I can clearly state that it is drawn this way because it must necessarily be this shape, this form, and this color.

It is starting to sound rather like Kandinsky, isn’t it?

The principle of inner necessity.

Painting must possess necessity.

Can a work that the artist themselves cannot firmly justify or explain truly have value?

To create “somehow” or “intuitively” is like working in a fog—it is not a healthy approach.

Can you explain how each form in Kandinsky’s abstract paintings was created?

Those of you who create abstract art—can you explain why each form in Kandinsky’s abstract paintings took the shape that it did?

In his writings, Kandinsky stated, “Through many years of cultivation and effort, I became able to select and create appropriate abstract forms.”

There is little doubt that many of the forms in his works reference things that exist in reality—seahorses, water fleas, wombs, sperm, and so forth.

That said, even I cannot explain everything completely.

That is precisely why I have pursued, not a “sensory” approach, but the question of how to depict necessary forms and colors through theories I myself have discovered.

Because abstraction does not depict concrete forms such as flowers or horses, abstract forms must exert a stronger visual effect on the viewer’s senses and possess greater expressive power—otherwise, there is no point.

I am convinced that I have clearly established this systematic theory for generating abstract forms for the first time in the history of art.

It was truly difficult—an endeavor that was genuinely without precedent.

And as it turned out, it took 45 years to establish it.